During our residency at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station, as part of the BioArt Society’s Ars Bioarctica programme, we developed a central component of the research underpinning Salt of the Times, a hybrid project that investigates memory, displacement, and materiality. Salt emerged as the element capable of linking places as distant as Argentina and Finland across the oceans. Our proposal focused on observing environmental change—particularly the process of Atlantification—in Arctic ecosystems, and on speculating about water (and ice) and salt as living archives of climatic, cultural, and ecological transformation.

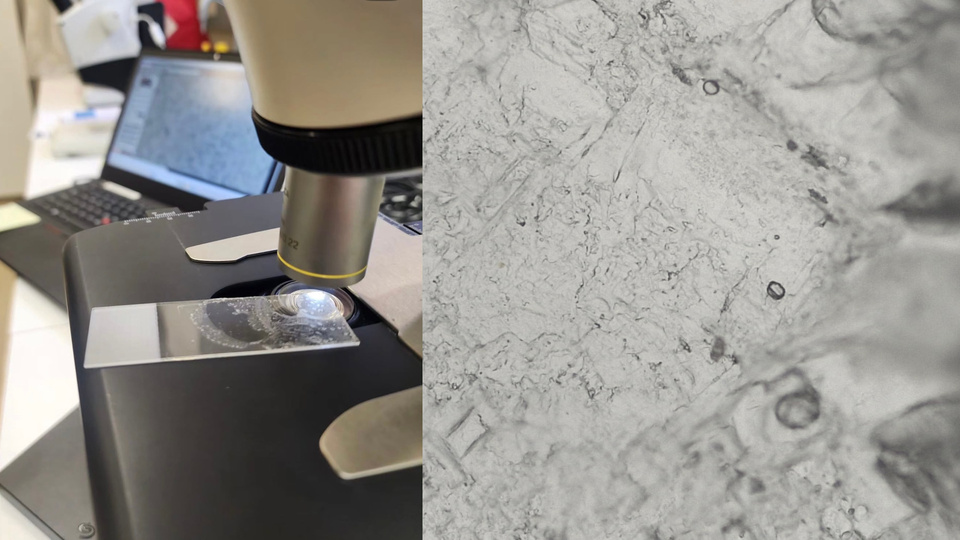

We crossed the border into Norway to collect seawater and salt samples, guided by the hypothesis that environmental archives are neither linear nor stable: they dissolve, intermingle, and are perpetually rewritten.

Atlantification refers to the growing influx of warmer, salt-rich Atlantic waters into the Arctic. This process reshapes three key gradients: a thermal gradient (greater heat moving northward), a salinity gradient (increased salt concentrations in deeper layers), and a density gradient (altered stratification).

A salt crystal is a trace of its dissolution history.

In Kilpisjärvi, thanks to the generosity of Hannu Autto and Anu Ruohomäki, we had the opportunity to visit a new station on Saana fell measuring carbon sink size, and we also hiked with Maija Sujala to Lifeplan, a biodiversity project. With her, we also learned about a fundamental process for understanding the material logic of Kilpisjärvi: cryoturbation.

Cryoturbation describes the vertical and horizontal movements of the soil generated by repeated cycles of freezing and thawing, a phenomenon that reorganizes sediments, minerals, organic matter, and even microbes. Landscapes, “literally,” move and reorganize.

In Kilpisjärvi, Salt of the Times converges at a critical point: cryoturbation demonstrates that the geological record is porous and that material memory can be reorganized by thermal processes. We then incorporated the idea of mapping this rewriting and translating it to other fields. What we understand as an archive is neither linear nor stable; cryoturbation disrupts it, stirs it up, and rewrites it.

Cryoturbation breaks, mixes, elevates, buries, and displaces. It is the ground thinking in slow motion and the cold writing upon matter. It mixes materials from different eras, creating temporal discontinuities: “ancient” layers appear on top, “young” layers sink. In geomorphological terms, it is a process of forced reconfiguration of the Earth's archive.

Nothing remains untransformed

Mixture then appears as a state where boundaries are neither lost nor maintained: they dissolve. They become unstable. And this instability is not an obstacle, but a condition that allows systems to continue acting. A system where everything is clearly separated is a system without the possibility of transformation. Only in mixture new configurations appear. The structure solidifies, but only to open up again.

What remains is not the form, but the capacity for reorganization.

There is no longer a “pure” natural archive; every archive is processual, dynamic, emergent, composed of material contaminations. Matter reveals itself to us as something not stable, but potential. Form is one of its possible manifestations; we are interested in speculating on its capacity to move between configurations, to dissolve and emerge, to mix and differentiate, to empty and condense. Matter is less an object than a movement. And movement does not occur “despite” form: it occurs through it.

Persistence does not appear as stability, but as a repetition of the process. What is maintained is not the form, but the system's capacity to continually reorganize itself. In cryoturbation, this persistence is evident: the thermal cycles are not interrupted, even though their visible manifestations change. The same is true for salt, whose crystallization and dissolution constitute alternating phases of the same chemical mechanism.

The world does not move towards a final equilibrium, but rather towards a state where it can always change again.

Based on the records of Arctic ocean salt observed through the station’s microscope, we are developing translations into 3D models and exploring crystallisation experiments.

WIP: Ecological memory: Salt can crystallize past changes (melting, water infiltration, pollutants) and store "layers of time" that can later be visually interpreted.

We are reading these images as prophetic objects. If we think of salt and ice as memory and transmission of information through time, what memories would we want to imprint?

Special thanks to

Leena Valkeapää, Hannu Autto, Anu Ruohomäki, Maija Sujala and Yvonne Billimore.